Sumber gambar: BBC Indonesia, EPA

Thick bushes now cover the ruins. Smooth paved roads traverse through them. Vehicles pass by in busy traffic.

The traces of liquefaction from September 28, 2018, in the Balaroa area, Palu, Central Sulawesi, are almost no longer visible. It's as if the remnants of the disaster have vanished, and perhaps our memories of the past disaster have also faded.

On April 26, 2024, we will commemorate the Disaster Preparedness Day.. With this momentum, we are reminded of the memories of the Balaroa disaster. It is also important for us to preserve the historical memory of disasters, so that we can continue to learn how to respond when a disaster occurs.

Balaroa in the Past

Before the Earthquake, Tsunami, and Liquefaction disaster struck Palu, Sigi, Donggala, and Parigi Moutong regions almost six years ago, the Balaroa area was inhabited by thousands of people who settled in Perumnas Balaroa, which was built in the 1980s.

No one anticipated that this densely populated residential area would become a mass grave for thousands of liquefaction victims.

The September 28, 2018 disaster revealed various stories about the Balaroa area and its origin. Balaroa, it turns out, has a long history of disasters, but its memory has not been passed down due to the erosion of oral culture.

Let's start with the name Balaroa itself. Balaroa is a local term referring to a plant with the Latin name Kleinhovia hospita. Balaroa is also known as Katimaha.

This small to medium-sized woody plant grows abundantly around river areas. Its leaves and bark are often used for traditional medicine, for example, to kill lice and treat internal diseases.

This small to medium-sized woody plant grows abundantly around river areas. Its leaves and bark are often used for traditional medicine, for example, to kill lice and treat internal diseases.

The name Balaroa itself indicates that the area is located near a river basin.

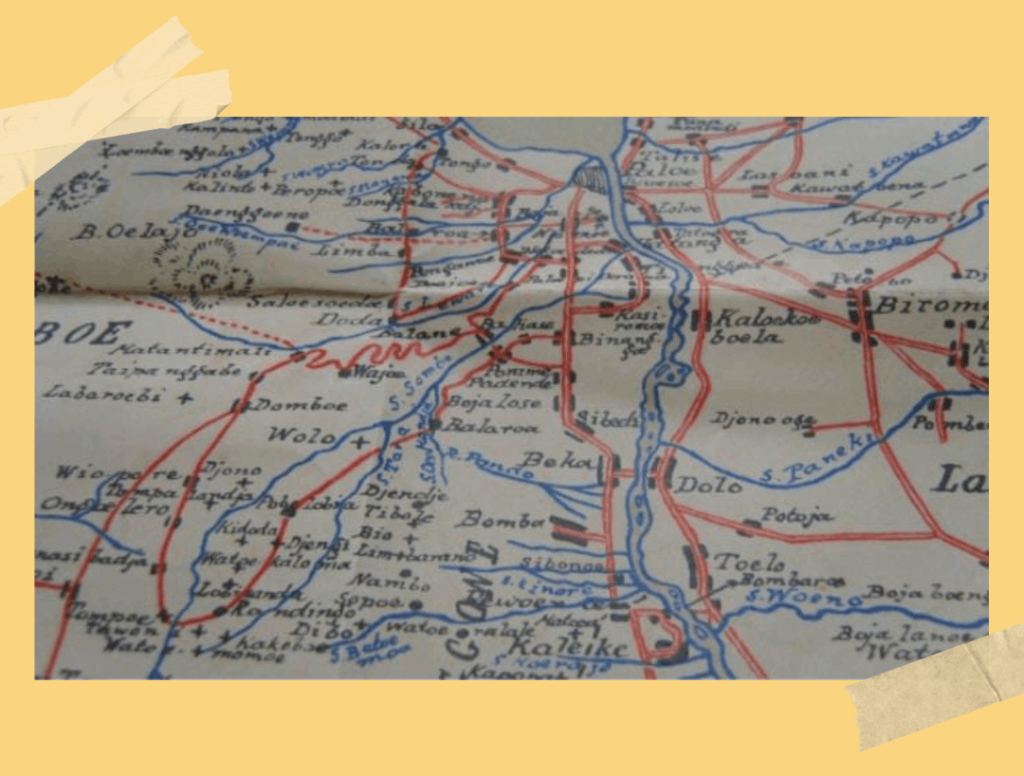

Iksam, an archaeologist who currently serves as the Head of the Cultural Office of Central Sulawesi Province, stated that on an old map of Central Sulawesi made by the ethnologist Albert C Kruyt in 1916, the areas affected by liquefaction on September 28, 2018, were originally river basin areas.

In that map, the Petobo area, which is now covered in mud, was the former Kapopo River Basin, also known as the Nggia River. Other areas affected by liquefaction, such as Jono Oge and Balaroa, were once the Paneki River Basin and Uwe Numpu River Basin.

Donna Evans, in the Kaili Ledo-Indonesia-English Dictionary published by the Cultural and Tourism Office of Central Sulawesi Province in 2003, translates Lonjo as sinking in mud or deep water. Subainda, a resident near Perumnas Balaroa, mentioned in Mohammad Herianto's book "Tracing the Name of Muddy Land in Balaroa," that in the Kaili language, Lonjo means muddy land.

Subainda said that in the past, Lonjo was not a settlement because of its muddy soil structure. He even mentioned that traders who wanted to sell their goods in the Old Bambaru Market had to take a longer route to avoid the Lonjo area. They preferred to pass through Kampung Duyu and Pengawu, located south of Balaroa, even though it was a farther distance.

Most of the residents from the Marawola Barat area, located in the mountains west of Balaroa, did not want to risk passing through Lonjo out of fear of sinking.

In addition to being known as Lonjo, the local community also often refers to it as Tonggo Magau. Mohammad Herianto quoted the late Andi Alimuddin Rauf, a community leader in Palu, as saying that this name originated from the large mud ponds owned by the Palu King's buffalos in that area.

On the eastern side of Lonjo, there is also the name Puse Ntasi, which means "center of the sea" in Kaili. The name originated from a salty well believed to be connected to Teluk Palu bay. This belief arose when the Palu King's buffalo fell into the well. After a few days, the carcass of the animal was found on the coast of Teluk Palu.

Memory of Balaroa's Disasters

In this 15-minute film, Mama Padja tells how her ancestors passed down the memory of the Balaroa disaster. Her story is identical to the stories told by Subainda and the late Andi Alimuddin Rauf.

The stories about the memories of Balaroa's disasters mentioned above are evidence that the people of Palu, especially the Kaili people, are familiar with the concept of disaster preparedness, as seen through the naming of places according to their characteristics.

The Kaili people name a place or area based on three aspects. First, the local flora and fauna. Second, natural or historical events. Third, the names of prominent figures. The September 28, 2018 disaster opened people's eyes, as well as the local community, to how toponyms serve as markers for areas considered to be at risk of disasters.

The National Disaster Preparedness Day

Considering the above facts, it would not be excessive if, on this Disaster Preparedness Day, local knowledge related to disasters in Palu is passed down to the next generation by incorporating it into the curriculum of educational institutions in Palu.

The Palu City Government, through the Department of Education and Culture, took a strategic step in 2019 by initiating the development of a Guide and Learning Materials for Integrated Disaster Mitigation Based on Local Wisdom in the 2013 Curriculum. Unfortunately, these teaching materials have not been further implemented in educational institutions.

This program aims to prevent and reduce the impact of disasters in educational institutions. The implementation of the SPAB program is regulated through the Minister of Education and Culture Regulation No. 33 of 2019.

Furthermore, the Palu City Government can also incorporate disaster mitigation lessons based on local wisdom into the local curriculum in schools. Based on Law Number 23/2014 concerning Regional Governments and Minister of Education and Culture Regulation (Permendikbud) Number 79/2014 concerning the Local Curriculum of the 2013 Curriculum, the local wisdom and cultural uniqueness in each region allow for the development of local curriculum for schools in their respective areas.

The Palu City Government already has teaching materials for disaster mitigation based on local wisdom. Now, we only need to wait for the government's commitment to implementing it in education. This is a necessity.It depends on the government's commitment to making it happen, with the spirit of "Ready for Safety" towards "Resilient Palu, Great Palu".

About the Author:

Jefrianto is a journalist and author of a book about the history of disasters in Palu titled "Nothing is Coincidental: Life Above the Palu Koro Fault". He is also an alumni of We Create Change Vol.3 organized by WeSpeakUp.org.